Embodied Carbon: Tech Set Like Concrete?

Carbon figures are being put on construction materials but what about the technology in the buildings? Mott Macdonald’s Pete Swanson is convinced we’ll soon need to answer for tech’s carbon footprint.

Interview:/ Christopher Holder

Embodied carbon? If you had visions of Han Solo in stasis… no, that’s ‘embodied carbonite’. Embodied carbon is a measure of all the carbon it takes for something to be designed, built, maintained and retired. As governments legislate CO2 targets, embodied carbon will increasingly be important. Like a weight-watcher counting kilojoules, every aspect of doing business will have carbon figures attached.

Embodied carbon figures have been estimated for building projects, providing another measure of how sustainable a new building is. Less common is an estimate of the embodied carbon of technology products.

The Australian office of Mott MacDonald – a multi-national, multidisciplinary consultancy firm – decided to have a crack at its own estimates, producing a report (‘Audio Visual Products’ Carbon Footprint in Buildings’) to outline its findings.

I spoke to Pete Swanson, Digital Tech Lead at Mott MacDonald, and prominent Australian #AVpeep about the report. The ‘take home’? “There’s a thing on the horizon; it’s quite far away; it’s going to take a while to get ready for it, so how about we start to make some progress?”

Sounds wise. Over a Zoom call I asked Pete to elaborate:

CARBON COPY

CH: What sort of contribution does technology have in the total embodied carbon of an office building?

PS: AV, ICT and other building technologies are incredibly carbon dense. We talk about the carbon density of concrete – typically 2.4t-2.5tCO2/m3. Because we use large quantities of concrete that carbon density per cubic metre multiplies into millions of tonnes of embodied carbon. But concrete is much less carbon dense than, say, a server. As we race into the age of artificial intelligence we’re gathering and generating much more data, and our server requirements are growing exponentially.

Not only that, once you’ve formed concrete, it stays in use for a long time. If you go to retrofit a concrete-framed building, you’ll retain the structure. But technology is replaced on much shorter cycles – every three to five years for frontline AV or ICT, with a few exceptional pieces of kit lasting five to 10.

It’s very likely that all embodied carbon associated with technology will need to be accounted for in the future. Because carbon equals cost, businesses will need to consider offsetting costs when purchasing carbon-dense equipment, noting that the cost of carbon credits is always increasing.

Our report is a call to mitigate that risk, but also to address an opportunity for businesses to realise a commercial and reputational opportunity by getting ahead of the curve.

“”

People don’t realise that technology is incredibly carbon dense. We talk about millions of tonnes of CO2 associated with concrete but concrete is much less carbon dense than, say, a server.

GROWING INTEREST

CH: Where are we starting from?

PS: Dell and Logi are doing some good work to calculate the embodied carbon of their products, but their data is far from comprehensive. Other than that, precious little carbon data is being produced.

In the very near future we expect that clients will be asking for carbon figures alongside cost. Which is why we carried out our own life cycle analysis to give approximate numbers that would be useful to our clients when making AV procurement decisions – considering the cost of carbon credits alongside purchase price.

Our sustainability and technology teams reviewed a typical bill of materials for a commercial office AV project. There are established lifecycle analysis techniques and carbon estimation tools used to assess the embodied carbon of buildings and structures. They adapted those techniques and tools to AV products – examples in the report show how complex AV devices can be. The analyses were vetted and validated by other sustainability team members.

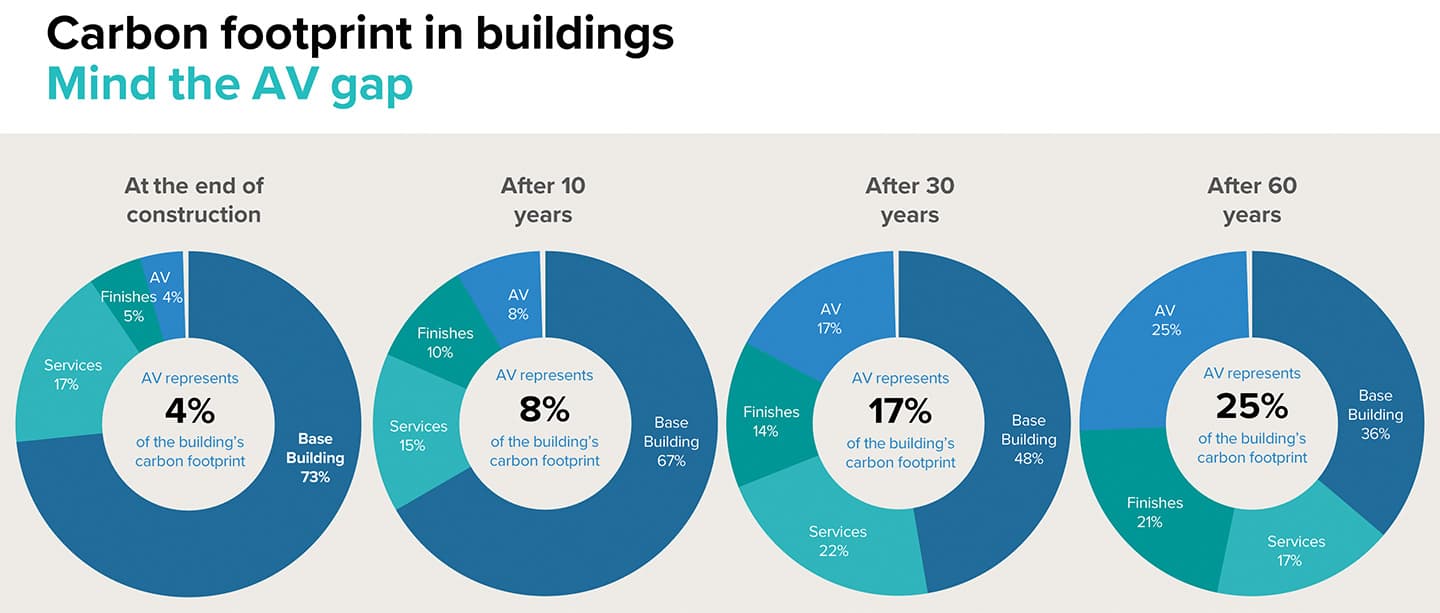

The Mott Macdonald study demonstrates AV equipment’s growing proportion of a building’s carbon footprint over time.

WHAT ABOUT SELLING STUFF?

CH: And what did you find in your report?

PS: A 75-inch display is basically a tonne of carbon. We’re not suggesting you don’t buy that big screen, but we are posing some questions: Can you get a display that embodies 900kg of carbon rather than 1t? Or, can you extend its lifecycle from three to five years, or maybe even 10? Carbon can be amortised better.

Then there’s the end-of-life question – and this is particularly true for networking equipment: can you downcycle the technology? A cutting-edge financial business may need the best of the best, requiring equipment to be upgraded after three years. But that three-year-old technology can be effective for businesses with lesser demands, as well as schools and non-profit organisations.

Once you start to realise that there’s an inherent cost, but also an opportunity, then you can begin to build different models.

Interest in carbon is growing thanks to a combination of policy, regulation, guidance and ratings, including NABERS, the National Australian Built Environment Rating System. The AV industry has been reticent, even resistant, and that’s understandable, because the industry is currently set up fundamentally to sell kit. Anything that doesn’t cheer that on is unlikely to be met with wide applause.

But there is an opportunity for suppliers and buyers alike. Higher quality, longer-lasting kit will have a higher initial cost. Once bought, suppliers will likely need to provide a higher level of service. And software solutions will become more important, including offsite hosting and SaaS – software as a solution – supported by energy and carbon-efficient data centres.

Carbon is becoming a business-critical consideration. Like all transformations, there will be innovators, early adopters and laggards. My point of view is that it is better to be a disruptor than to be disrupted.

Mott Macdonald: mottmac.com

“”

Our report is a call to mitigate that risk, but also to address an opportunity for businesses to realise a commercial and reputational opportunity by getting ahead of the curve

CASE STUDY: LOUDSPEAKER

A loudspeaker is composed of a timber enclosure, a metallic grille and electronic components. A manufacturer shared its preliminary findings regarding its loudspeaker carbon emissions. This information was used as a base for other similar products.

The findings were as followed:

Total weight: 9.55kg

Timber enclosure weight: 2.9kg

Metal grille weight: 0.65kg

Electronics weight: 6.0kg

Total A1-A3 carbon emissions: 51.39kg CO2e

A1-A3 carbon emissions per kg: 5.4kg CO2e

*A1-A3 encompasses materials, transport and manufacture of the product

RESPONSES