Beatlemania Grips The Powerhouse

Text:/ Robert Clark

Images:/ Daniel Sievert

To mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Fab Four landing in Australia and infecting scores of otherwise-straight-laced teenagers with Beatlemania, Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum has staged an exhibition that celebrates the before, during and after of this pivotal cultural event. Bringing the music, performances, merchandise and everything in between back to vivid life required some real ingenuity from the museum’s technical and creative team.

THE LONG & WINDING ROAD

“The idea came to us about three years ago,” says the exhibition’s curator, Peter Cox, “when we realised that in 2014 it would be 50 years since the Beatles toured Australia, and what a good idea it would be to do an exhibition about the impact of what was a very significant event in the 1960s.” In order to truly explore that impact, it would be necessary to resurrect the technology through which Australians experienced the Beatles at that time. This meant scouring through archives, back-lots and eBay to find objects from that era, and giving them a bit of a 21st-century nudge.

I CALL YOUR NAME

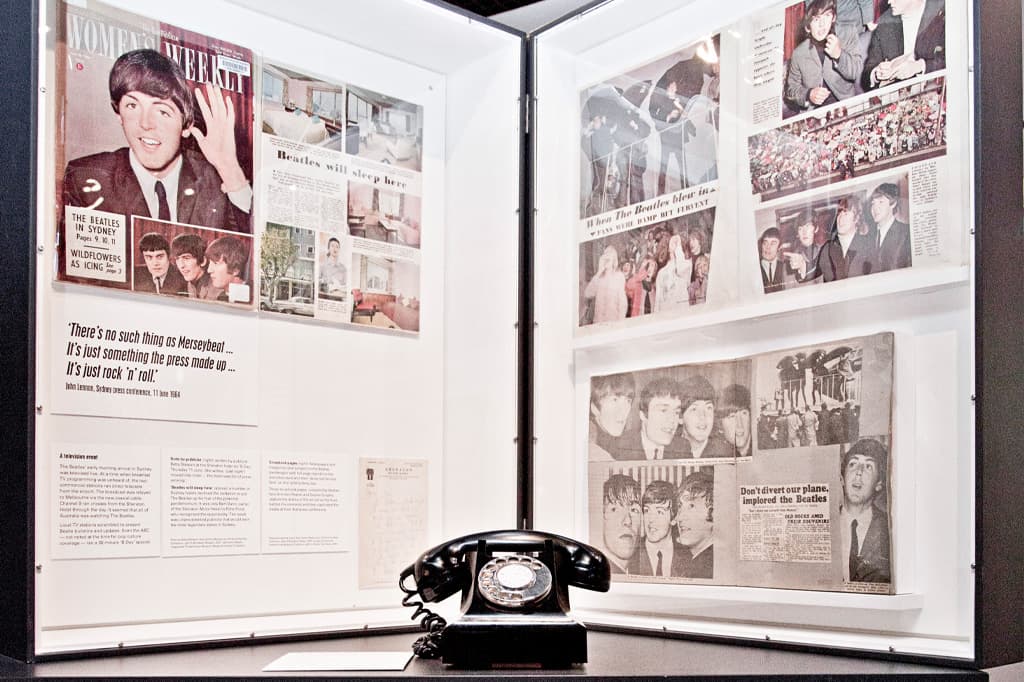

One such iconic object is the black Bakelite telephone, which you find nestled all around the space. Exhibition designer Malcolm McKernan explains the rationale: “Peter Cox’s original brief was that he wanted to bring back that original feel; that you were transported back to Australia in the ’60s. So I thought the Bakelite telephones were a great device for listening to audio interviews.” The phones are not only aesthetically interesting and relevant, but also offer a very discreet delivery mechanism for audio in what is quite a large, open space. McKernan adds, “Being the Beatles, there’s a lot of sound involved in the exhibition, so sound containment has been a real challenge.” The dual functionality of these phones is clever, but it’s what’s underneath that is the most remarkable.

To allow six different interviews to be selected on each phone, senior electronics technician Owen Conlan had to provide the units with a multi-channel delivery mechanism linked up to the dial. Originally, Conlan planned to install a Raspberry Pi (credit-card sized single-board computer) in each phone, “but it meant that I was going to hack the phones too much,” he says. They found that taking the ringer out in order to insert the Raspberry Pi meant that the audio signal was no longer interrupted by lifting and replacing the handset. “When we took that functionality out it just didn’t feel the same,” he says, “it just didn’t feel like a proper phone. So we went the other way of leaving the phones intact and putting the controller outside.” What this meant in the end was finding an old telephone exchange and linking it up to a modified controller. Each of the six .wav audio files were assigned to a channel via a software interface on a laptop, which could be disconnected once the programming was done, leaving the controller freestanding. What results is a seamless, user-friendly and novel way of listening in.

(above) A couple of Mole Richardson ‘Pups’ (possibly even older than the Beatles themselves) dress the stage for the screening of the Festival Hall concert footage.

DON’T BOTHER ME

Another solution to the openness of the space was the decision to build sound booths in which people could sit and immerse themselves in video content. Designer Malcolm McKernan modelled these closely on listening booths from record stores in the ’50s and ’60s, so they blend seamlessly into the exhibition. The video replay is set up very simply, with iPads connected via their headphone jack to a small amplifier and a single mono speaker. The speaker is in the top right corner of the booths, on the opposite side to the opening, as Conlan decided this position would provide a good buffer from outside noises. Felt and Autex acoustic fabric clad the inside of the booths to help with acoustic isolation. Conlan says, “This doesn’t totally cut out the sound from outside, but it reduces it considerably, so it’s been quite effective.”

TELL ME WHAT YOU SEE

In keeping with the early ’60s aesthetic of the exhibition, it was decided that archival footage from the group’s visit would be best viewed through a conventional AWA television from the late ’50s. As in the case of the telephones, there were a few hurdles to be overcome in combining old technology with the new. Conlan knew the picture tube wouldn’t be unserviceable after many years of disuse, so they removed the CRT and the main electronics chassis. The original plan was to find a monitor that they could insert into the existing frame, but this proved too awkward. Conlan and his team eventually found a neat little work-around. “I got hold of a piece of rear projection material,” he explained, “which I stretched across the mask that went around the face of the picture tube.” The next step was to insert a short-throw projector, which took a bit of wrestling given that their Mitsubishi unit was a touch too large. With no option of buying an alternative projector, however, the team built a new back for the set that placed the projector the required throw distance from the screen. It’s all very neatly done, and from the front it still looks like it’s 1959.

THE INNER LIGHT

There is an abundance of historical documents from posters to contracts to diary entries in this exhibition, and each has strict conservation requirements to remain in good condition, low exposure to ultraviolet chief amongst them. This is largely solved by using UV filters and LED light sources, but as McKernan explains, careful planning has gone into choosing exactly what type of LEDs get used: “The conservators tried to get us to have lighting at about 50 to 60 lux, depending on the age of the material. But if an object is going to be on display for one year and then back in the archives for 10 years, they can balance it out over that entire period, so maybe we can pump it up to 70 or 80 lux.” The showcases are custom built to accommodate the sensitive materials. “A lot of the showcases we painted internally quite bright white,” he says, “so it bounces a lot of the light around and you don’t get a hot spot of light – it’s quite diffused. This works quite well with the LED strips we have, which have a little opaque diffuser on them.”

HEAR, THERE & EVERYWHERE

Dominating the main entrance to the exhibition is a four metre-wide screen carrying footage of the Beatles’ concert at Melbourne’s infamous Festival Hall during the tour. A Mitsubishi 8000 lumen projector rear-projects onto the screen, while powered –speakers are enclosed beneath the stage. The audio level is by necessity very low, and visitors must wear headphones if they want the full immersive experience. Again, the openness of the space dictated terms, as McKernan explains: “We went in quite early one morning and set it up to what we thought would be a really nice level. Then we went walking around the museum and realised very quickly that it kind of took over the whole museum. Even in the boardroom we could hear it, so we had to drop it right down. You’d expect for a screen that big to have it a lot louder, so that’s why in the front row we’ve put headphones, because it’s actually quite an amazing sound.” McKernan admits some directional speakers would have helped a great deal, but unfortunately the budget didn’t stretch that far.

WE CAN WORK IT OUT

The rear-projection screen in the old AWA television is actually an off-cut from this large screen at the entrance. Indeed, much of what is done at the Powerhouse requires thrifty solutions and the innovative use of equipment, as budgets are often tight and turnarounds are quick. A good example is Conlan’s adoption of the $40 per unit Raspberry Pis, which are used throughout the museum to drive video content.

Perhaps ironically, innovation is the name of the game in this exhibit that revels in nostalgia. The overall effect is one of deep immersion in the style, colour and sounds of 1960s Australia, which appears to have been irrevocably changed by those four lads from Liverpool.

MORE INFORMATION

Showing at the Powerhouse Museum Sydney until 16 February, 2014 then Arts Centre Melbourne 8 March to 1 July, 2014

Web site: www.thebeatlesinaustralia.com

Raspberry Pi: www.raspberrypi.org

RESPONSES