Interactive Cinema

A UNSW-based research group heads ‘down pit’ with amazing results.

Text:/ Tim Stackpool

Images courtesy UNSW

The use of realistic virtual reality simulations for training is not so uncommon these days, especially in the airline industry. In fact, no commercial pilot is presented with his or her licence until they have racked up hours in various simulated scenarios, separate from their actual in-sky training hours. Today, however, the technology is being reworked, re-engineered and completely overhauled to give experience to students and personnel in more hazardous and uniquely challenging environments.

One of the more impressive developments has been devised by the iCinema Centre for Interactive Cinema Research. Based at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), it has been applied to recreate surface and underground mining scenarios. Resulting from unique inter-disciplinary collaborations between various faculties, the simulator project has generated multi-million dollar sales and has attracted immense international interest across the mining sector. Head of iCinema Research, Professor Jeffrey Shaw believes “interactive cinema is a new form of cinema that integrates all forms of digital media allowing the audience to interact with and become part of the cinematic experience”.

NOT A CANARY IN SIGHT

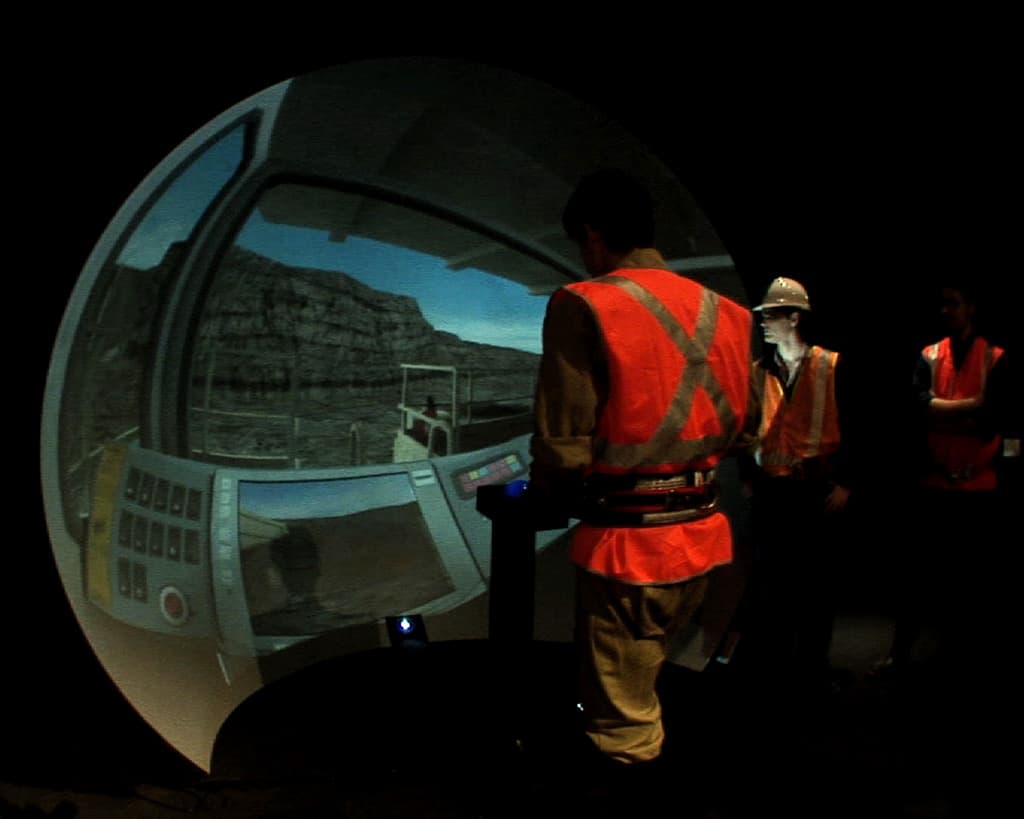

Similar to a giant sophisticated computer game, the participant is surrounded by a stereoscopic 3D environment, and subjected to a frighteningly real, interactive virtual mining scenario where they encounter all of the hazards that exist in the real workplace. Initial introduction to the immersion environment is reportedly an uncannily realistic experience. In an underground mine vehicle moving along a tunnel, for example, the subject can see in all directions, just as if it were a real location. You can feel as if you could reach out and touch the roof bolts. You can maneuver past static vehicles and industrial plant equipment, or walk up to continuously operating heavy mining machinery. During the experience, the subject interactively learns operating procedures and to recognise danger signs and situations. Similarly, in an open cut simulated mining environment, perhaps at the wheel of a giant haul truck, subjects learn to maneuver heavy loaders and be alert to how easy it is squash things (such as people… smaller trucks) from a raised driving position several metres high.

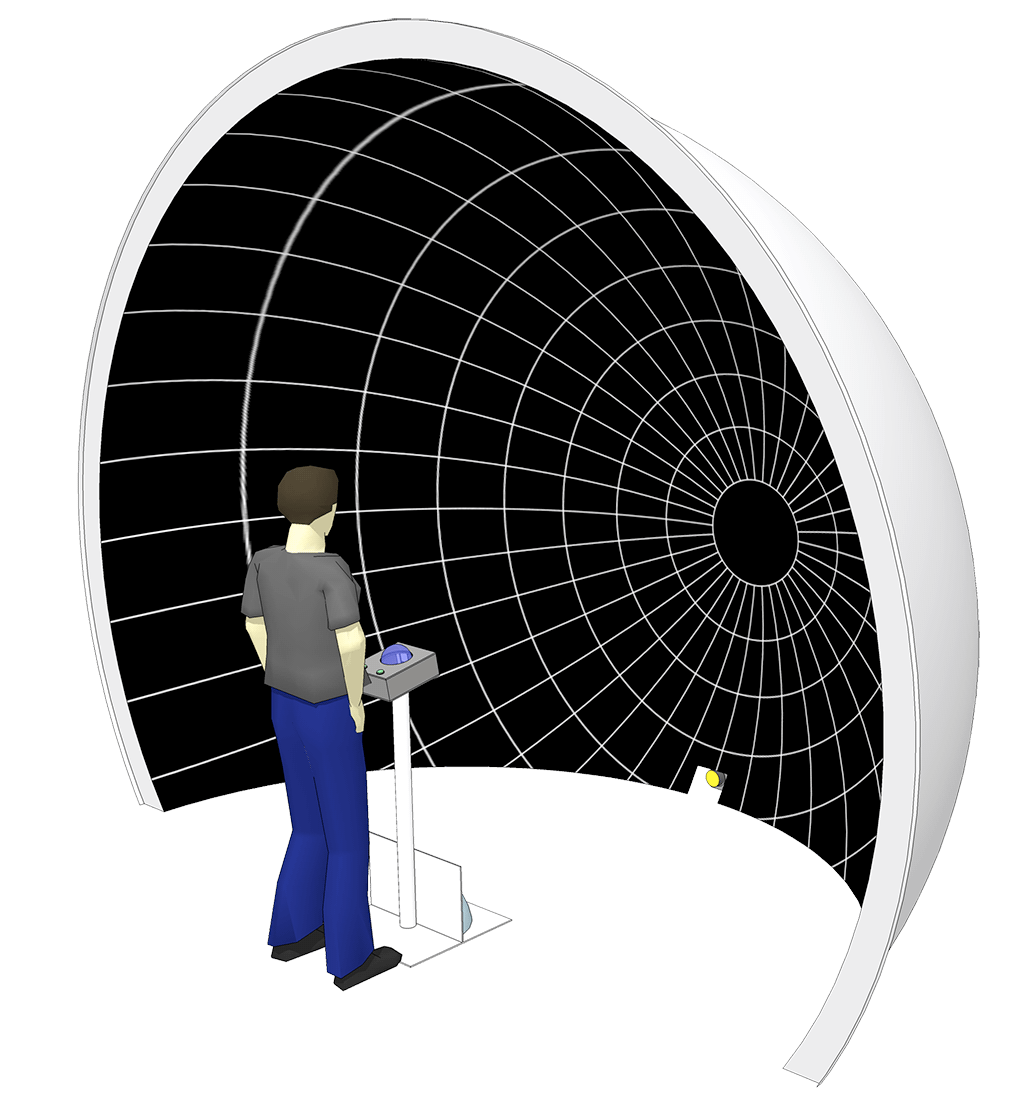

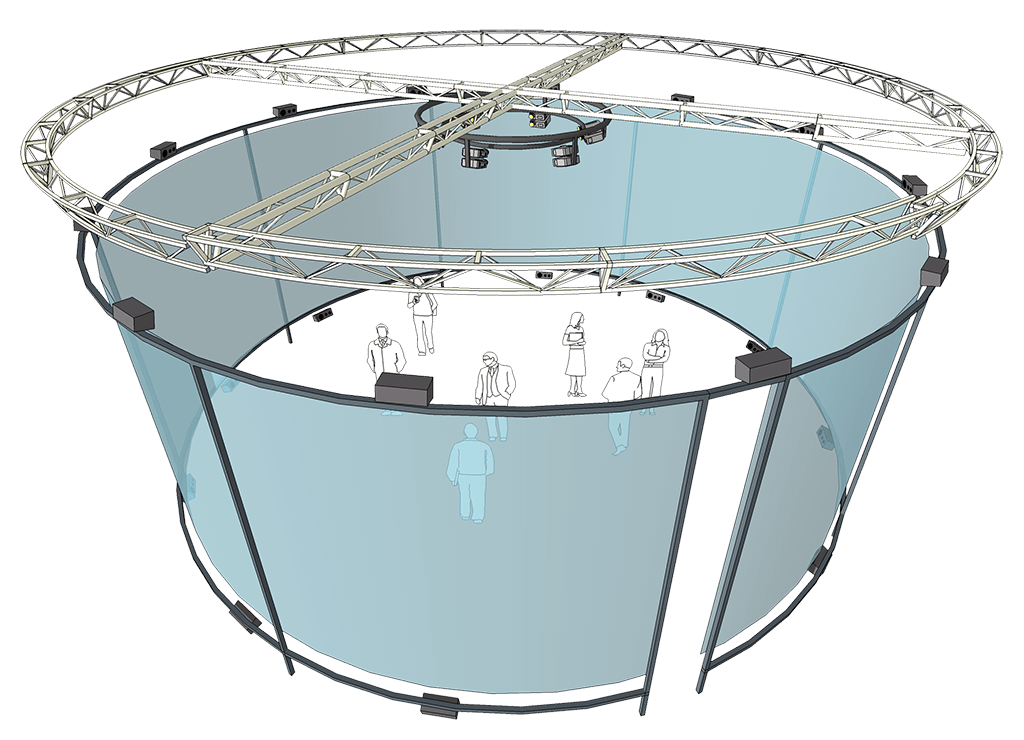

The experience is divided into separate modules, each recreating mining environments of various scenarios. These can be displayed in multiple theatre modes including a 360-degree ‘Advanced Visualisation & Interaction Environment’ (AVIE) version for group training of up to 30 students and a 180-degree version for individual training sessions, known as iDome. The AVIE experience is contained in an 80sqm space surrounded by a 4m-high x 10m-diameter circular screen. The smaller iDome offers a compact visual environment, and is configured as a 4m-diameter fibre glass hemisphere, standing vertically in front of the participant, filling their peripheral vision. A high-definition projector, surround sound and a custom user interface completes the equipment inventory.

(above) iCinema takes the viewer into an immersive virtual reality environmemt through 360-degree 3D projection.

Image courtesy of Jeffrey Shaw

RICH SEAM OF DEVELOPMENT

Development of the technology started in 2002 and is constantly in a state of refinement. Mechanically, the screen rigging system was designed in 2003, but there have since been upgrades to the truss structure to compensate for different site requirements (and the ability to reduce the shipping requirements for international trade shows where the system is demonstrated). The 3D rendering, edge blending and screen geometry correction, which incorporates the interaction engine (known as AVIEBase) was completed in 2007. In 2009 the software now includes an audio system with basic 12-channel surround with the capacity for 24.2 surround.Marc Chee, an iCinema systems engineer, indicates that many more features are being introduced. “Infra-red tracking follows people’s positions within the space and we’re working towards visual gesture recognition,” he said. “The engine includes advanced animation features, with a pipeline for importing motion capture data, high-resolution panoramic videos as well as employing various artificial intelligence algorithms to move virtual entities within the space.”

The project has run entirely within the UNSW, with three schools being involved: The College of Fine Arts, the School of Computer Science and Engineering, and the School of Mining Engineering, particularly their VR group with the development of the mining simulation modules.

The immensity of the project with its various facets is staggering, not least of all the visual aspect of the simulation. “Warping and blending, interaction with different hardware devices and media streaming all presented their own challenges,” noted Damian Leonard, Project Manager with the development, and well they might – one application has more than 400 video files playing simultaneously across the VR screen. Another major challenge has been designing a control and video preview system capable of remote monitoring and troubleshooting. “We support four sites in NSW from Sydney,” he said. “So we’ve set up systems that can monitor, troubleshoot and resolve an extended range of hardware from our Sydney office.”

NUTS & BOLTS

The system developed at UNSW was the first stereoscopic, fully cylindrical system in NSW. There are other systems which have been developed since then, but the iCinema architects believe theirs was the first of its kind to use software-based blending and warping.

In terms of projection, F20 and Cineo F30 projectors from Projectiondesign are used, with the company being a partner in the research. The control software was written entirely in-house and controls the various devices over TCP/IP, serial and DMX. The system also uses an ‘Interaction Device’ for user input that was also designed in-house. It consists of a joystick, several buttons and an inertial orientation reference pointing device, titled the ‘Intersense Inertia Cube’. This allows the user to move in 3D space as well as point in any direction in the virtual space.

Components such as projector mounts, screen frames, and user interaction devices (devices incorporating joysticks, accelerometer devices etc) were designed by the team. The virtual reality software is unsurprisingly based on an existing 3D engine, but over the years the developers have created many additional add-ons and plug-ins. This includes magic such as various artificial intelligence algorithms, improved animation engines, specific device controls and so on. One notable development is the ‘Spherecam’ system. This is an integrated audiovisual recording system capable of taking panoramic video at 14,400 x 1200 pixel resolution as well as surround-type 12-channel audio tracks.

“”

One application has more than 400 video files playing simultaneously across the VR screen

iDome is a single-person virtual reality environment where a single projector covers a 4m-diameter fibre glass hemisphere that completely fills the participant’s visual field

AVIE is a spectacular multi-person virtual reality environment based on a 10m diameter x 4m high circular screen seamlessly covered by six pairs of projectors using polarisation to separate the left and right stereoscopic images. Audio comes from six stereo pairs of speakers.

MORE IMMERSION

As time marches on however, the development team is looking towards the opportunity of improving the visual immersion experience, especially in the realm of 3D imagery. “More feature-rich active stereo projectors are appearing on the market this year, with more lightweight shutter glasses. These may be used rather than the current passive solution”, says Ardrian Hardjono, Technical Operations Manager with iCinema. “Our AVIE and iDome systems are constantly evolving and being upgraded with the appropriate technology, as we have deployed eight AVIE systems in the last two years, which has given us the opportunity to improve on limitations of the initial system setup in 2003”, he added.

Behind the computer code running the entire experience, most AVIE installations follow a standardised deployment configuration. Namely, around 12 passive stereo pairs of projectors (being polarised and matching the participants’ 3D glasses) are arranged on a circular truss ring above and inside a 10m-diameter cylinder of a silvered projection screen. A cluster of image generators controlled by a master PC then coordinates the interaction devices and audio. Twelve speakers in a ring carry the audio around the screen. Being a learning environment, there is also a separate cluster of four PCs which capture data then correlated into usable information for review and further appraisal of the participant’s reaction and aptitude when faced with various scenarios. “The infra-red cameras assist with building a virtual representation of all objects inside the AVIE space by capturing data from many points of view and algorithmically rebuilding the live scene in a computer-based 3D model”, Ardrian Hardjono reports. “Artificial intelligence algorithms are then able to analyse this model at an interpretive layer to pick up human gestures and other crowd-based movements.” The interaction device with joystick, buttons and pointing device completes the rig.

OTHER INDUSTRIES DIG IT

This type of development opens up a whole range of industries to virtual reality training. Underwater safety training for offshore drilling rigs is one such area. In fact, any hazardous environmental training can be enhanced by this technology. Conceivably, other types of environmental conditions could be incorporated into the experience such as heat or cold, aromas and weather conditions. Architectural planning is another sector, and even tourism, with simulators allowing access to remote areas that are too difficult to reach or inaccessible due to cultural or heritage restrictions. “Entertainment and gaming are also two fields that could greatly benefit from our systems,” Marc Chee added.

This iCinema technology developed at UNSW is truly staggering, with attention being gained worldwide. As Professor Jeffrey Shaw notes, it is beyond virtual reality: “It plunges the audience into an immersive reality,” he said. “There are no barriers between the virtual and physical, and the narrative is created spontaneously.” Currently four AVIEs and 12 iDomes are operating in purpose-built training sites across NSW, particularly deployed by NSW Mines Rescue Stations operated by Coal Services Pty Ltd. Between them, the systems will use more than 80 of Projectiondesign’s F20 SX+ and F30 1080 projectors.

The advancements made by the researchers and developers at UNSW have truly changed the way in which audiences will view and relate to immersive cinema forever. Apart from that, their contribution to the increased safety training in hazardous environments is immeasurable, especially when you consider that it could ultimately be lifesaving.

RESPONSES