Meyer Constellation: Full Circle For Auckland Venue

The story of the first installation for Meyer Sound's Constellation acoustic modification system in Australasia has an elegant symmetry.

Text:/ Derek Johnson

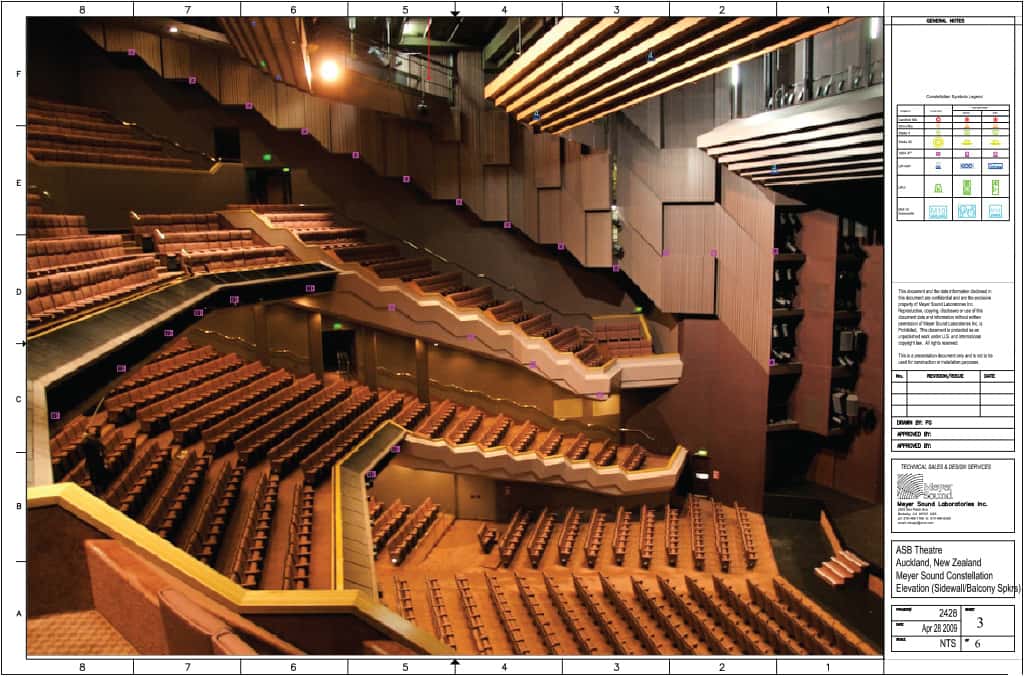

Auckland’s ASB Theatre, part of the Aotea Centre performing arts and events centre, opened in 1990. A lower roof than ideal kept costs down, but necessitated a custom electronic reverberation system to make up for the missing acoustic volume. This wasn’t a great success; the venue opened with a concert starring home-grown diva, Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, but after the system upset a visiting conductor, there for the venue’s second concert, it was turned off.

Consequently, the hall’s acoustics have remained a compromise ever since. Five years ago, it was decided the problem needed to be tackled head on. Kerry Griffiths, Head of Technical Operations, Aotea Centre describes it as a complete refurbishment of everything front of house of the proscenium: “Acoustically, the audience area was not very good. Aesthetically it was pretty tired and in need of a spruce up.”

Raising the roof was once again not considered financially viable. “The majority of the improvements were around the natural acoustic in the room, with Meyer’s Constellation acoustic system giving us the variable aspect you couldn’t get with just the room”, reports Griffiths.

CONSTELLATION’S NZ GENESIS

In one of those early audiences was Dr Mark Poletti, then at Auckland University’s Acoustics Research Centre. His experience of the hall’s acoustic, and the response to its short-comings, led him to research and publish academic papers that ultimately outlined an elegant approach to acoustic enhancement that is both revolutionary and, in concept at least, easy to understand. The product of that research, the Variable Room Acoustic System (VRAS) is licensed to Meyer Sound by NZ research powerhouse The Callaghan Innovation, where Dr Pelotti is now a senior research scientist. VRAS is at the heart of Constellation: the story comes full circle.

Constellation is not an artificial reverberation system. Rather, it ‘samples’ a room in real time through a large number of carefully (and discreetly) positioned small DPA reference microphones (76 at the ASB). A newly-generated soundfield, created in a natural manner by adding many finely-tuned delays to the input, is output through a constellation (268, including subs, at the ASB) of critically-placed Meyer loudspeakers.

Constellation’s synthesized delays interact in a way that mimics real-world audio and become a natural component of the room’s resulting reverberant field, as treated audio blends with the room’s original audio. Mic and speaker positions, together with processing calibration ensure that feedback and phase cancellation are not issues.

It might be a simple system to describe but Constellation requires serious DSP grunt to make it go. This is provided by Meyer D-Mitri ‘digital audio platform’ units, running the latest VRAS. These high resolution audio processors have a sample rate of 96kHz, 24-bit AD/DA conversion and up to 64-bit floating point processing. D-Mitri offers realtime networking, simultaneous multichannel processing and is hugely customisable.

The system can be configured to give the impression of any imaginable acoustic space, big or small; D-Mitri also allows complex panning for special effects and cinema surround sound simulation. The ideal, though, is to produce an environment that suits the room and doesn’t distract the audience by, for example, sounding too ‘big’ for the space. The hardware is visually inconspicuous, with most of the mics and speaker cabinets in reasonably unobtrusive locations.

RAISING THE VIRTUAL ROOF

In the case of the ASB Theatre, Constellation simulates the acoustic of the space, had the roof been that five metres higher. The ASB is home to NZ Opera and the Royal New Zealand Ballet, so a traditional classical acoustic has been welcomed by performers, audiences and critics alike. That said, ASB hosts a variety of events, and Constellation can be tweaked to provided acoustics suitable for such events as stage musicals and spoken word conference sesions

But Constellation goes beyond correction: the acoustic has been rendered consistent throughout the hall. Untreated, the under-balcony areas had been dead and oppressive. Treating the balcony acoustics wasn’t an option. Now, without sounding unnatural or distracting, the acoustic under the balconies is as involving as the rest of the hall when Constellation is engaged.

On-stage performers also benefit from the hall’s new, well-rounded sound – a cumbersome hardware shell has been replaced by a ‘shell’ of Constellation mics and speakers. Being enveloped and involved in the acoustic inspires musicians to produce a more involved performance. The artistic feedback loop is completed by the performers being better able to hear the audience, and the audience better able to hear each other. The point was made that audio feedback can help the audience enjoy themselves more. The imprecise term ‘vibe’ comes to mind.

Overall, there are no distracting acoustic hot (or dead) spots, yet localisation of sound sources in the ASB’s Constellation soundfield is uncompromised.

VIRTUOUS CIRCLE

Inevitably, installing Constellation was a collaborative effort, including Aotea Centre’s operations team, lead by Kerry Griffiths, on-site integrator Bartons Sound Systems (theirs was the joy of installing many kilometres of cabling, the mics and the speakers), and Marshall Day Acoustics, responsible for the physical acoustic remodelling in consultation with architects and builders. Constellation was commissioned in stages and last year integration and testing of the on-stage hardware brought the installation to completion.

The CV of Meyer’s John Pellowe, Constellation voicing specialist, includes Grammy awards for classical audio engineering and being front of house engineer for the Three Tenors. “All our best projects have been fantastic partnerships with acoustics consultancies such as Marshall Day. During the voicing process, the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra has been rehearsing at the hall, allowing us to make adjustments in response to the musicians’ advice.”

Marshall Day’s Peter Exton, a violist, also applauds the APO’s input: “Working with an orchestra has been a treat, allowing us to fine tune the acoustic for different repertoire, and in response to musicians’ feedback. The APO generously provided four full mornings of rehearsals, so we’ve tried a range of repertoire — Stravinsky, Brahms, Wagner, Beethoven and Mozart, getting progressively smaller in terms of orchestra size to hear a range of texture.”

Yet Pellowe adds: “We have to be very careful when we provide different reverberant presets. We can make this room ridiculously long, which is great for some shows. But it’s my feeling that for a broad range of repertoire there is one setting you can leave with the client. Of course, if someone who wants to fine tune the strength, the length and the warmth, that’s fine, if they have the ears to do that. But once you hit the right numbers, the reference acoustic will work — as it does here — for a broad range of repertoire.”

Visit the Callaghan Institute’s website (www.irl.cri.nz) to search for abstracts of Dr Mark Poletti’s acoustic research. Those related to VRAS are handily listed here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VRAS#Technical_Papers

CUSTOM SYSTEM

Harley Richardson of Meyer Sound Australia notes that while Meyer would rather install Constellation in a new-build venue, most systems are retro-fits, with each space presenting its own problems, solved by a bespoke system. “It can be installed by a third party but Meyer Sound tests everything the installer does, and tunes and voices the system.”

So while Meyer would prefer a dead room — less than half a second with not many early reflections — putting back what’s required for a given application, that luxury doesn’t often present itself.

Pre-Constellation, the ASB was notorious for uneven reflections: “You could sit in one seat four rows back and hear really loud vocal and the person next to you would be wondering what the performer was saying because all the reflections were missing them.”

John Pellowe reckons the theatre’s original reverb time was 1.3 to 1.4 seconds: “Quite low and not ideal for classical music.”

Tuning requires listening, but ears are an essential tool right from the start. The initial rough design is made in consultation with everyone concerned with the installation, with some compromise in response to the physical requirements of the renovation. Pellowe: “The integrators — Bartons Sound System — put the system in, while the hall was being renovated. There was new flooring and new seat covers, and the under-balcony seating profile has been changed. The hall has been transformed.”

Testing the installed Constellation system is a scientific process, ensuring all the equipment is in the right place. “Then we go into a bit of a secret session where we calibrate the system, which we don’t say too much about.”

Tuning is rather more subjective. “Once it’s calibrated, I come along and mess it all up!” says Pellowe. “I voice the system, which takes a long time. We can never be certain of the parts played by the wooden panels or the loudspeakers because we’re doing the two things at once, but it doesn’t matter. I define an environment where people like to play, and where they feel comfortable. We want the end users to have something they feel they’re a part of, rather than having some arrogant guy present them with their hall.”

UPON REFLECTIONS

Pellowe referenced the work of Marshall Day co-founder Sir Harold Marshall on the importance of ‘lateral fraction’ to our perception of acoustic spaces. “He discovered something many of us knew but which no-one had documented: the acoustic energy coming from the sides is more important to our perception of localisation, imaging and so on than the energy coming from above.” Marshall Day pioneered ways of calculating a hall’s lateral fraction, information that’s now widely used.

Marshall Day’s Peter Exton again: “Technically, the sound of the room is a combination of direct sound from the musicians, reflections from the side walls and ceilings — early reflections — and reverberation, the sound energy that’s bounced off many surfaces. The energy of the reverberant tail becomes less and less after many bounces. Early reflections, those that arrive up to 80ms after the original sound, have travelled less than 27m compared to the direct sound. The ear can’t separate them — they have a finite response time – so the initial sound seems stronger, and we hear that as increased clarity. This is good for ‘crisp’ music, or if you want clarity of speech. After about 80ms, the ear’s response clicks in and we hear that as a fullness of sound – the reverberant tail. If this later sound, and even some of the early sound, comes from the sides of the room, and if the signals are different to our two ears, we feel immersed in the music. And if the reverberant energy comes from the sides, we feel much closer to the musicians and more involved in the musical performance. As acoustic designers, we can change the character of the sound that the audience hears in a room.”

But it’s VRAS that allows Meyer to work with these ideas electronically. Pellowe: “VRAS lets us produce much more complex reverberation, all mathematically derived. We’re not doing anything weird to the sound, there’s no time-variance. Apart from the 3ms of latency in D-Mitri, everything is time constant in Constellation. The microphones are linear, the signal processing is linear and time constant, and the loudspeakers are all linear: within their designed operating range, what goes in is what comes out — a John Meyer obsession. All the components are neutral so when you install them you really can, with confidence, calibrate the system: we’re capturing the true acoustic of the room.”

Pellowe explains further: “We don’t transfer any reverberation from the auditorium. All of the reverberant energy on stage is captured on 12 microphones, above your head. What we do take from the stage are early reflections; we progressively delay them and attenuate them throughout the building. The hall is divided into two zones because it’s more than 27m wide. All the microphones and loudspeakers in each zone are related to one another and they’re never more than 27m (80ms) apart — and we try to get closer than that. With bigger zones it’s impossible to organise time arrivals. With a Mahler symphony which has off-stage trumpets, for example, it’s important that those time arrivals are correct across the building and not just going out from the stage. You have to zone it otherwise you can’t organise the time arrivals in the right way. We have to organise the electronics exactly as a physical space. It’s one of the things that makes Constellation rather more expensive than some people would like, but it’s the way we have to do it.”

Even so, a small or medium performing arts centre would likely find installing a Constellation system saves money over building the size of space they’d like. Constellation would allow the venue to be configured for many purposes with no compromise. This approach saves resources, and running costs — a small space means lower heating or air conditioning costs.

In closing, Meyer Sound’s John Pellowe says: “I’ve been working with Constellation for seven years and the ASB Theatre has been in many respects the most interesting adventure for all of us, because of its origins, where it started, and how it inspired Mark Poletti to write his thesis that led us to Constellation.”

COMPANIES INVOLVED

archoffice: www.archoffice.co.nz

Meyer Sound Australia: www.meyersound.com.au

Marshall Day Acoustics: www.marshallday.com

Bartons Sound Systems: www.bartonsound.co.nz

RESPONSES