AV in Sepia

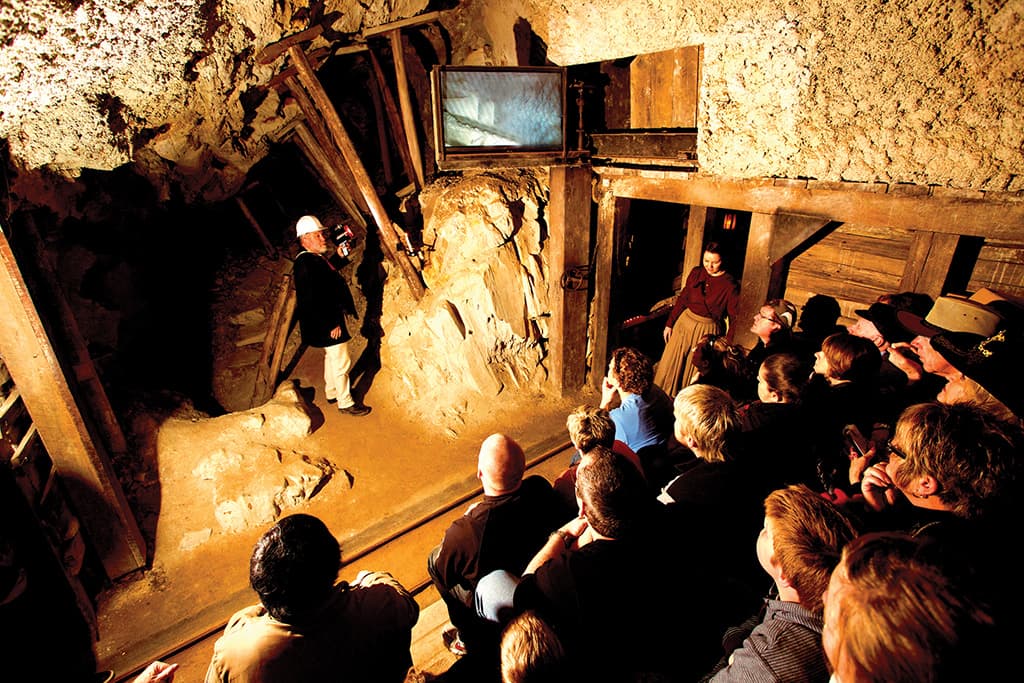

Sovereign Hill: an historical attraction served by an AV history lesson.

Text:/ Mandy Jones

Images courtesy Sovereign Hill

Sovereign Hill is a faithful representation of life in 1850s Victoria at the height of the gold rush. Through cleverly-recreated working displays of the Ballarat township, gold mines, authentic activities such as gold panning, and impressive son et lumiere presentations, the history of the goldfields township is brought convincingly to life, 364 days a year.

A back of house tour of the site with Adam Reid, manager of technical services for Sovereign Hill, is like reading an ice core-sample of technological milestones. The gamut of equipment and systems in use and running day after day is surprising. At one end of the spectrum, an Apple PowerBook 190 (running Dataton Trax) and 486-processor computers happily run complex automation sequences, in stark contrast to new video projectors and AMX touchpanels in other displays. There is even one museum display still running a video replay off analogue laser disc.

Adam has worked at Sovereign Hill for 10 years and had a previous association with the tourist attraction while working for Lightmoves during the installation of several displays. “I work in a museum that uses technology to tell stories of life on the goldfields, and the technology we use has to fit seamlessly into the presentations,” he explains.

Adam heads a team of four full-time audiovisual technicians who are responsible for the day-to-day maintenance and repair of the 26-hectare site’s many displays. Their brief is large – in addition to the expected vision, lighting, audio and control systems, they are responsible for programmable logic controllers, pyrotechnics, gas effects, hydraulics, water, oxy acetylene detonations, automation trucks and set dressings. Add to that the complication that most of the systems are either in outdoor all-weather environments or 20 metres underground in confined and dust-ridden spaces, and this is no easy gig.

While aspects of the operations, particularly new displays, are ‘smart’ and provide diagnostics and usage reports via AMX NetLinx, the majority of the systems are reliant on daily checks, resets and constant vigilance – a labour-intensive undertaking, especially over such a large site.

BLOOD COUNT? 600 PER ANNUM

Blood on the Southern Cross (BOSC) is one of the audiovisual showpieces of Sovereign Hill; a large-scale sound and light show staged over four different locations on the site, it depicts the events leading up to the pivotal Eureka Stockade in 1854. Incredibly, the 90-minute show runs twice a night (around 600 times a year), and without technical operators.

The show starts in the Voyage to Discovery auditorium where a tour guide introduces the show and presses the Start button, firing up an elderly but still functioning AMX system, which triggers three Panasonic PT-D4000 projectors to create a large seamless image, with audio playback through a Bose PA. Projected images of actors are added via two additional projectors and motorised screens. Content is managed over three different systems – an Alcorn McBride DVM2 digital video machine, a video server custom built by The Shirley Spectra that runs four feeds of video, and Roku solid-state video players for a further two feeds of video off SD card. This is the new system which replaced the triple analogue laser disc and three-gun CRT projector system, which itself displaced the original Electrosonics-controlled 18-projector 35mm slide show.

A Sennheiser GuidePORT audio guide system provides foreign language translations of each stage of the BOSC show via hand-held units. Available in French, German, Chinese and Japanese, the receivers can also be used for hearing impaired visitors utilising an English feed.

The second stage of BOSC takes place in The Diggings and immerses the audience in an automated experience made up of over 90 channels of dimming, 15 channels of audio and four gas effects, all controlled by ShowCAD on a 486 computer. Inside every tent and hut is at least one light. Practical lanterns, smoke machines and snorkel-lift lighting towers hidden inside huts and water tanks all add to the effect.

The final stage of BOSC is a 40-minute, 500-cue, sound and light spectacular, set over a 12 hectare (30 acre) panorama. Again, the guides press Start and AMX triggers an Akai DR16 hard disk recorder that provides audio playback and SMPTE timecode. The show runs off a dual-redundant ShowCAD system on two 486 PCs locked to the SMPTE to ensure the lighting, audio and effects are all synchronised.

“There’s something like 300-odd dimmer channels and 60 or so switched channels, plus hydraulics, flags that raise, trucks that move, power switching for audience seat heaters, 15 smoke machines, two video projectors, GoldenScan HPEs, a water screen, a whole lot of gas flames and explosive effects, 15 channels of audio including the four foreign languages; and it’s all fully automated,” says Adam.

Incredibly, Adam can count the number of show cancellations over the last 10 years on just one hand, and even then, most were due to floods or power outages rather than critical system failure.

Day-to-day maintenance of BOSC includes refilling LP gas tanks, pyro and fogger fluid. Unlike the other displays, BOSC has the luxury of two scheduled annual maintenance shutdowns (a week in February and two weeks in August) during which all the lighting fixtures are cleaned, re-gelled, re-lamped and re-focused, and set pieces such as canvas tents are refreshed. Major works like replacing lighting towers, gas burners and even rebuilding entire structures like the Eureka Hotel (which burns down every show) are also completed during these periods.

MINING ITS OWN BUSINESS

Throughout the labyrinthine tunnels of the mine, kilometres of Dynalite DyNet, DMX and speaker cabling run through PVC pipe painted to look like a steam pipe. Practical lanterns, handmade by the on-site tinsmiths combine with 150mm-spaced Cliplight fitted under timber handrails to illuminate the path. Making use of some ancient decommissioned Dynalite Studio 12 analogue dimmers from BOSC (replaced by LSC ePRO dimmers), the salvaged dimmers are used to run a Brian Shirley-designed four-circuit random chase to create a flicker effect in the practical lanterns.

JBL Control 23 speakers, inadvertently but effectively shot-creted, are barely visible throughout the mine. Providing soundscape playback from a Tascam unit, the speakers are triggered by 12 Dynalite infrared sensors spread along the course used for audio ducking.

“The sound effects in the mine are designed to be heard in the distance so you can’t quite hear where the sound is coming from, whether it’s voices or digging sounds. When the Dynalite sensors are triggered by approaching visitors, they tell AMX to turn the speakers off in front of the group as they approach and turn the speakers behind them on,” Adam explains.

“”

an Apple PowerBook 190 runs complex automation sequences, in stark contrast to new video projectors and AMX touchpanels in other displays

ISO STOPE

At around 22 metres below the surface, a display depicts the mining practice of stoping, where after the gold has been removed from the rock walls a large opening is left behind and timbers are used to prop the mine ceiling. When the main tunnels were dug in the 1970s to create the mine, an actual gold rush era stope site was uncovered. In order to activate the historic display for visitors, a plasma screen and JBL Control 23 speakers are installed to show explanatory content. But instead of just showing pre-recorded footage, Brian Shirley went one better and developed what is now referred to as ‘Stope-Cam’. Several generations later, Adam’s team has continued tinkering with the invention, making improvements and adding new components.

“We took a normal handheld 50W spotlight with a lead acid battery in the back of it, and replaced the light source with a 60˚ very flat 3W LED light source. We stuck a Sony video camera on top of it, and got a household video transmitter, stripped the casing off it and put it inside the body, and powered it all off a 12V battery,” Adam explains.

Stope-Cam transmits a surprisingly good live picture to the plasma screen and enables the tour guides to climb into areas of uneven terrain inaccessible to visitors, while explaining the stoping and rock-bolting techniques through close ups of the digging site on screen. A radio mic on the Stope-Cam even enables tour guide commentary via the JBL Control 23 speakers.

“We were going to use the live camera for the first part and then switch to some pre-recorded footage, but the live camera has been so successful we’ve continued with it. I think we’re up to Stope-Cam Version 23C and the next generation is currently being developed, mainly because we can’t get spare parts for the current one anymore,” Adam adds.

AV GOLD MINE

The newest display within the mine at Sovereign Hill is Trapped, a multi-sensory experience telling the story of the Creswick mine disaster of 1882. Trapped received a special commendation at the recent AVIA awards – check out Chris Holder’s in-depth look at Trapped in Issue 10 of AV or on the AV website.

Despite the disparity of technologies, Sovereign Hill’s audiovisual displays work at the press of a button, and the visitors love them. Adam’s multi-skilled team and their suppliers go to extraordinary lengths through programming and maintenance to enable non-technical staff to run the complex displays day in, day out. To some extent, they are victims of their own success.

“The tour guides press a button and it works, and they have no idea how much work has gone into making sure it works… every time. But, that’s how it should be,” Adam muses.

RESPONSES