Every Pixel is Sacred, Part 2

Blended Projection – Part II

Text:\ Paul Newton

Specialised software lies at the heart of all multi-image systems. The application looks and feels like any other timeline, layer-based application such as After Effects, Final Cut Pro or Flash. The difference is that the multi-image systems are sending live graphics to projection hardware instead of simply creating a file to be played back later on a computer or website. These applications are truly ‘live’. Programs such as Watchout, OnlyView, Pandora’s Box and Wings Platinum are the most common applications and have become the industry standard within the event market for creating widescreen multimedia shows. I will primarily refer to Dataton Watchout in this article due to the extensive exposure I have had with this product over the years.

All these systems operate in a similar manner – dedicated display servers ‘power’ each segment of the blend and are controlled via a ‘supervisor’ production machine or controller. If you are creating, for example, a three-projector blend you will require three display servers – one per projected image. This essentially means that you have the power of three high-specification computers and the combined resolution of their graphic cards to play and control your multimedia show. The connectivity between all the servers is usually a gigabit network switch and UTP (CAT5a/6) cable which makes live event control a breeze – servers can be located backstage and easily be controlled via a laptop at front of house. These systems can also often be interfaced/controlled via custom made controllers, timecode, MIDI, DMX or sensing devices such as motion sensors.

DATA MIXING AND PROCESSING

While all the previously mentioned systems can be cabled directly to the projection devices, it is highly recommended, to utilise a multi-output vision mixer such as Barco Folsom Encore or Vista Systems Spyder before passing onto the projectors. Traditional mixing consoles allow a multitude of inputs to be sent to a common output. Encore and Spyder are different in that they allow multiple inputs to be seamlessly processed/routed to a series of linked outputs. Within the live event world – these consoles are required to layer additional input sources as PiP (Picture In Picture) on top of the hi-res background (e.g. powerpoint/keynote presentations, tape rolls and live camera). It is possible to input live sources directly into these systems – and free up the need for a complex, expensive mixing system – but the quality is pretty average … and often delayed by a few frames – resulting in very obvious lip-synch errors. The other important function of the mixer is to allow backup system streams to be sent to screen in the event of a system crash.

These days, consoles are usually digital, using DVI and HD/SDI (High Definition Serial Digital Interface) connectivity ensuring signals remain clean and fast. Video latency (frame delay experienced while signals are being processed) can never truly be eliminated, but it can be reduced so that it is virtually unnoticeable to the untrained eye.

Another advantage of using a live mixer is flexibility. Being able to mix and cut live sources in a show whenever you need is a lot safer than relying on a cue on a timeline. Mixing consoles also have different wipes and effects, frame storing, extensive scene presetting ability and PiP enhancements such as bordering, drop shadowing and movement.

PROJECTOR PLACEMENT

Projector placement must be very precise. When blending, projectionists rarely utilise lens-shifting or digital key-stoning to correct the image. Each projected image must be optically ‘square’ to perfectly overlap with the adjacent projection. With this sort of accuracy required for installation – projectors are often rigged with the assistance of laser measurers and spirit levels. If the projectors are flown, a single, unbroken line of truss is highly recommended as separate trusses increase the chance of one of the projectors physically drifting. If you have a single line of projection truss, and the truss moves for whatever reason, the whole blend will move together and resettle to its previous position (assuming that there is solid two to four-point attachment to the truss with rigid clamps, so it therefore becomes ‘part’ of the truss).

If projecting front or rear from towers, the stability of the towers is essential. A mere 1mm or 2mm movement at the tower results in much larger movement on screen. Complete isolation from the public is imperative – the towers need to be erected in ‘no traffic’ areas and bordered with bollards if possible.

PROJECTORS

Three-chip, high-powered (10,000–20,000 ANSI) DLP projectors should be the technology choice for this sort of stuff. You can just get away with single chip DLP projectors – but you will experience poor colour reproduction in some parts of the colour spectrum due to the use of an internal colour wheel to create colours with these projectors. This inability to reproduce true-colour is particularly noticeable with warm tones such as skin tones, sepia, etc). This can be a big problem if you need to use a warmer colour palette with your graphics or utilise lots of live camera in your event.

The ambient noise level of the projectors should be factored in to the show design. Three-chip DLP projectors are usually quite a bit louder than single chip or LCD projectors, so you’ll need to try and separate them from the audience.

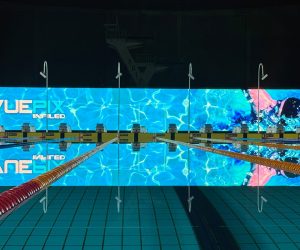

SCREEN

Screen selection is very important and is the final piece of the puzzle. The video companies that involve themselves with this work usually have their own screen inventory that they rarely share with their competitors. They’re not really items freely available on the dry-hire equipment rental market in Australia. Blend projection screens are typically 2.5:1 – 4:1 in aspect ratio and usually custom made to suit the average-sized venue … and the average corporate client budget. Typically, three to four projectors are required to fill these screens.

High quality, seamless projection screens are an expensive, yet essential, part of the equation. Cheap, incorrectly gained screens, manufactured from cheap material should be avoided – the screen is the final piece of the puzzle – there is no point getting perfectly timed, coloured and focussed pixels this far and not giving them a good place to sit.

The structural integrity of the frame is also an important factor. Frames that are old and tired (and mistreated) will not support a tight flat screen surface. The screen must be perfectly flat – a warped screen will result in obvious alignment and focal compromises – remember, we can’t use any digital manipulation of the image to get us out of trouble here.

Avoid rear project blending if possible. It’s very difficult to avoid hot-spotting with rear projection and, I believe, it spoils the effect. Front projection allows a more uniform projected image because the light is ‘bouncing’ off the screen as opposed to transmitting through it.

Projecting onto cycloramas is commonplace when images need to be over 10-25m wide – there are very few screens of this size available on the rental market. Cycs only really work as projection screens when they are kept taut with counterweights. Drafts and even air conditioning can slowly suck the cyc in and out resulting in focus and alignment issues. Creating truss squares and wrapping them in a cyclorama or similar cloth is probably the best method of mimicking a screen if you can rig them and find a neat way to deal with the excess.

Curved screen blending is also possible, but takes twice to three times as long to install. Most curved screens are a ‘surface only’ – they have no frame to dictate the radius of the curve. Rigging the surface usually requires truss that needs to be very accurately rigged to maintain a constant curve. The projector trussing has the same issue. Working with a single line of projection truss and a flat parallel screen is so much simpler!

Mapping the displays to a curved or other irregular shaped screen can be very time consuming and adds another large layer of complexity to an already complex task. The amount of processing to make all of this happen will often add considerable delay to the signal path and make elements such as IMAG (Image MAGnification via a live camera) very hard to incorporate due to lip syncing.

STAFF

You need clever people to do this stuff – your average AV company will be not be staffed nor stocked with the correct equipment to do this properly. The technicians that setup these events are a rare and talented breed and know their equipment and the signal path very well. You need to engage technicians that live and breath projection and do it all the time. This type of work is much more specialised and far less forgiving than traditional video work – if you don’t get it right – it’s very noticeable.

There are very few companies in Australia that specialise in this sort of installation. They include amongst their number Haycom Staging, Sloution Red, Electric Canvas, Massteknik and TDC. One of the pioneers of projection blending in Australia, and an example of how it is done properly is Technical Direction Company, for whom I worked for several years. I know that their attention to detail and servicing of their huge range of projectors and control equipment is exceptional, and I believe that this is the main reason for their dominance in this area. Projects are setup, colour balanced and tested in their theatre before they leave the warehouse, minimising onsite trouble-shooting or fault finding. It’s this kind of approach that you should look for in a supplier.

In summary, you need to make sure that you:

- a) engage a good video supplier that regularly tests their equipment.

- b) allocate a healthy budget to the projection system and content creation – this work isn’t cheap, and nor should it be!

- c) find an experienced graphic studio that ‘gets it’.

- d) involve clients early and work out a storyboard as soon as possible.

- e) test, rehearse, test, rehearse.

I was working on an event in Singapore with a very abrasive American producer 10 years ago that kept referring to ‘EPIS’ amongst his team. It seemed to be a touring ‘term’ that they kept amongst themselves during the four day event. We ultimately bonded on the last night of the show, and he finally told me what it meant. Every Pixel Is Sacred. Too right.

RESPONSES