Jinan Games

Local sports carnival.

Text & Images:/ Paul Collison

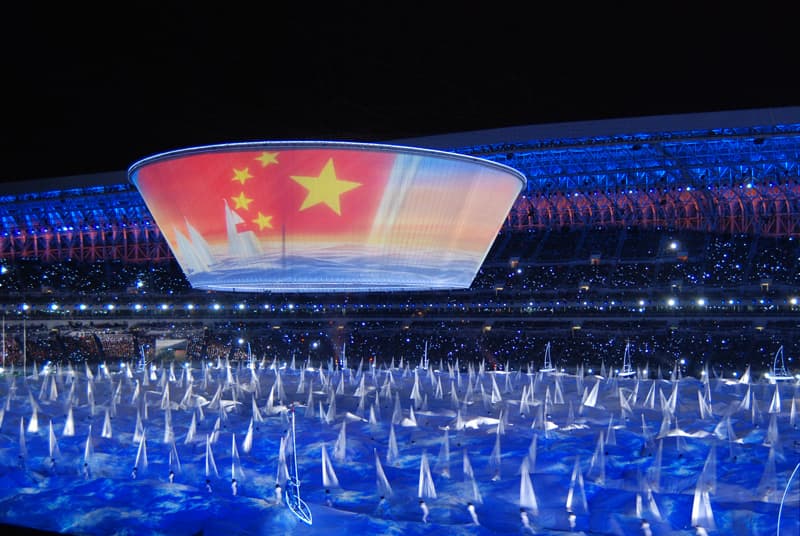

The world could take a leaf or two out of China’s book on how to celebrate an occasion. Sure the Beijing Olympic ceremony was seen by 594 million people live across the globe, but how many people saw the opening to last year’s Table Tennis Championships in China? Not many outside the region one would assume, but that didn’t stop the Chinese from putting on a show that was massive by any world standard. The same can be said of the 11th National Games opening ceremony on October 16th in Jinan, China. Not many outside of China witnessed the show. However, with an estimated television audience of 188 million, it was certainly a huge event for China.

LIGHTING

With a complement of over 1600 moving lights, this was a large lighting system in a relatively small stadium. Think more Sydney Football Stadium, rather than the MCG. There was always going to be a huge impact with that many fixtures in such a small space. The performance area was essentially the entire field. The space extended from the outside of the running track to the centre of the field. Being a broadcast event the audience and architecture needed to be defined as both a background and a feature.

Six horizontal trusses spanning over 300m each provided lighting positions in the roof: two to light the audience from the rear, and four close to the leading edge of the roof for the field. On top of this there was the old faithful balcony position, which provided an opportunity to light the roof and the lower audience areas in addition to the performance area. The last position, and possibly the most important when it comes to lighting performers in this sort of scale, was the edge of the field. As a pseudo footlight come sidelight position, this provides a great opportunity to light your performers without lighting the floor, thereby providing the designer the chance for at least some contrast between performers and the floor. This also aids in allowing any projection on the floor surface to be read properly.

Control was via an ever-faithful grandMA series 1 system. There were five active consoles operating across three sessions, each with its own backup. A classic distribution of 39 network signal processors around the stadium, linked via an optic fibre network, ensured accurate control over the entire show. Chief Lighting Designer Weng Chun Pu admits that the grandMA system was the only choice given the scale of show. “The programming style of the Chinese programmers stems from the Avolites platform. The grand MA system allows us to program in that style but control many more lights.”

PROJECTION

A battery of 270 custom built LED source film projectors were used to create 52 discrete images on the field as a backdrop to each segment. Yes, you read it correctly, an LED source, projecting through film. The LED projection units were a custom build by Zhi Gao in Hang Zhou China. Each unit consists of 110 x 5W 6000K LEDs. Based on a similar process to that found in the well-known E\T\C PIGI projection system, these LED projectors have a single roll of film material within which all keystone distortion must be pre-corrected. Each unit is DMX controlled and occupies only six control channels.

Weng Chun Pu explains that for the creative director, the projected images were the cohesive part of the show, “Each image took the audience to a new place. This was important to the telling of the story. Extra care had to be taken with the lighting so as to not affect the image – either live or on camera.” That’s not an easy feat when you consider that at times there were 5000 performers on the field, and that at best there was 300 to 400lux of light on the field from the projectors. There was some colour inconsistency in the output and colour rendering of the projectors, however it was interesting to see LED successfully used as a source in this type of application.

“”

it was interesting to see LED successfully used as a source in this type of application

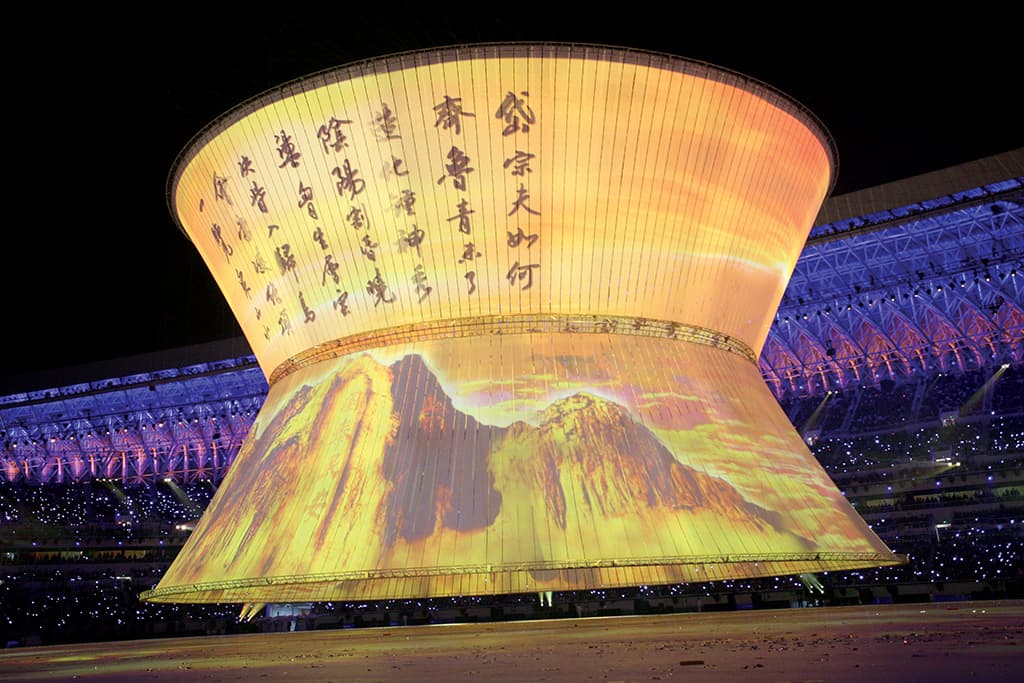

STORM IN A TEA CUP

In the centre of the arena was a large projection surface supported by four circular trusses; two of 50m diameter and two of 35m. Between each 50m and 35m circle, 15m strips of white nylon, approximately one metre wide, created the projection surface. Small gaps between the strips allowed for some wind to pass and gave the surface the flexibility to invert and change shape throughout the performance. This was achieved by simply changing the trim height of each truss. It was quite a simple but ingenious design that allowed for an easy reconfiguration of the space.

In the standard formation, the screens resembled an hourglass: wide at the top, tapered in the middle and wide at the bottom. This flexibility came at a cost. Even though there were small gaps in between each strip, the entire surface still acted as a big sail. Anything stronger than a three-knot wind would distort the shape and move the surface. Consequently lining-up became a nightmare. Once done, the following night the wind would ease and the surface would sit in another position. Although frustrating for the technicians on the ground, their tenacity proved fruitful as the end result was exceptional. Having a projection surface with an area of 1.2 square kilometres gave the space an animated core which the entire performance was centred around.

The upper part of ‘the teacup’, as it became known, was covered by 48 Barco XLM HD30 (2048 x 1080, 6.3kW Xenon lamp, 27k ANSI lumen) projectors. The projection surface was broken up into 24 areas, each area being allocated a pair of double-stacked XLM HD30s for increased brightness. At a throw distance of roughly 120m per projector the result was spectacular. Amazing to the point where the screen became too bright in the context of the show and needed to be pulled back in level to match the rest of the lighting on camera. The XLM 30HDs were fed via a Watchout system which took care of all the blending and warping. The lower part of the screen was lit with more LED Projectors with texture that matched the appropriate content on the upper part. A massive onsite editing team modified content day and night, right up until last minute. The same media creation team was responsible for media creation for the LED projectors.

AUDIO

A distributed line array system delivered audio to the live audience. The PA for the stadium consisted of four different types. A Meyer Milo system looked after the VIP seats from the arena floor. The remainder of the lower bowl was filled with a locally manufactured LAX line array similar to those used for the Beijing Olympic ceremonies, while the upper bowl was covered by two other locally designed and manufactured line arrays. At FOH, a Soundcraft Si2 console ran all monitoring and broadcast sends, while a Yamaha PM5D looked after the stadium.

Without live music and dozens of headline talent, the audio was a relatively simple affair. There was a surprisingly small input list, consisting of microphones for protocol segments and some live singers flying above the arena for the finale, in addition to the replay devices. Audio replay was run from a ProTools system that also looked after all time code, click tracks and choreography audio.

It was interesting listening to the PA as a foreigner. It seemed that all the nasty mid frequencies were pushed at the expense of clarity. It often sounded too loud and the midrange really sat in your face. Mandarin is tonal based and is often described as almost singing when enunciated correctly. It is not clear why the Chinese favour this type of audio, however it seems omnipresent in the region.

AUTOMATION

As with most public events of this scale, an automation system rivalling that of any outdoor spectacular you’ve seen of late was built from the ground up. Since the Sydney 2000 Olympic opening ceremony, nearly every large-scale public event has had some sort of flying system. Some are complex, while others simple but effective. The system in Jinan was definitely the later.

To start with, there needs to be some sort of mother structure to support the system. Often this is not easy as these types of production are seldom thought of when designing and constructing a stadium. In this instance, steel wires from the roof above the audience joined at a hub in the centre of the arena. Once this structure is in place, the mechanical lines can be installed. Large electronically-controlled winches were placed on the ground outside the stadium.

Two steel cables per ‘line’ are then run up to the roof and diverted to the hub, from where the cable is diverted 180° back to another winch. This then allows you to push and pull your point across the stadium. In order to add a vertical position to your point, a secondary line is run out to the first point. You can now drop a piece of scenery while moving it into the centre of the performance space. Now repeat this a hundred times and you have something close to the Jinan system.

The technique for the teacup screen was much simpler as there was no need to move it laterally, only up and down. Each circular truss was suspended by up to 16 support points. Built by Long Ying Automation, a well respected company that provides automation services for many film and television projects in China, the system was driven by proprietary control software.

“”

A battery of 270 custom built LED source film projectors were used to create 52 discrete images on the field

BIG PROPS

What large scale Chinese show would be seen without large props and lots of LED? The Color Company of Beijing were not only charged with supplying all lighting and vision services, but also with set design and construction. This gave them the unique ability to really integrate these designs into the show and incorporate control back to the lighting system via wireless DMX. Beijing Color is not like your normal lighting supplier. They often focus on only one project at a time and devote almost 100% of their resources to that particular event. Overlooking multiple aspects of the event allows them to utilise labour and other resources more efficiently. The result is a comprehensive focus on the show at hand and the synchronisation of efforts across the board to deliver a show.

Like the Olympic Ceremonies 12 months previously and 400 kilometres up the road, this show was big, but followed the same keep-it-simple rule. There was flying, more lights than you can point a DMX cable at and a video screen to make many an event producer squirm with glee. Add to this an excess of fireworks and enough to PA to fill two stadiums and you have the makings of a huge show, but underscored with simplicity. Above all, it was a show for the people.

Too often it seems, we try to produce shows that are technically amazing. But do the audience really get wowed by a thousand moving lights doing a complicated chase, or are they equally excited by scores of people moving in time waving flags and smiling? In this instance, it seems it was both.

RESPONSES