On Your Marks, Get Set…

The Nine Network’s Olympics set sets new records for sports hosting

Text & Images:/ Paul Collison

The Olympics are the pinnacle of so many elite events other than Olympic sport. There are the glamorous ceremonies, massive corporate pavilions and events, city-wide architectural installations, arts festivals, and, of course, the most complicated and cutting-edge television broadcast of hundreds of sports events over a period of four to five weeks. Newcomer to Olympic sports, Australia’s Nine Network, was in the thick of it in London leaping on to a new trend in television news set design.

Of course I’m talking about the set of ‘London Live’, the centrepiece of the Nine Network’s 2012 Olympic Games Coverage. This was the hub of the 17-day coverage and a place where athletes would be interviewed both pre and post competition and presenters would throw from one sport to the next for almost 15 hours of live television every day.

The set was the brainchild of Alex Rolls, creative director for Nine’s Wide World of Sports. Well aware of the trend in European shows over the last few years to utilise large-screen support, Rolls wanted a set and within it a visual surface that could interact with the presenters as well as form a panoramic backdrop and ultimately, form the basis of the flagship set. Rolls turned to Stuart Anderson, Senior Lighting Director at TCN9 in Sydney, and in turn, video company Big Picture to help realise the dream. That dream, of course, entailed a really big screen!

LED BY TODAY

There is a precedent to the big screen concept a little closer to home. The Today Show set at the TCN9 studios in Sydney has a 3.75mm pitch Unilumin LED screen. This screen has played an important role on the morning shows at Nine in 2012. At a 3.7mm pitch, the screen is the tightest LED pitch currently available. However, the first question always has to be ‘LED or projection?’. Just because LED was the solution in the Sydney studio, would it also be in London? The benefits of LED are widely known: it’s brighter than projection and less susceptible to washout from stray light sources; LED has better contrast and has the advantage of being a predominantly black surface. Projection, on the other hand, can provide much higher resolutions and looks cleaner, avoiding issues like moiré. The main problem with projection, however, is the throw distance from projector to projection surface. The studio in London was tiny, as so many studios are. Rear projection was not an option as there was less than a metre at some points behind the surface, while front projection was problematic as it tends to interfere with hosting positions, particularly in small studios. LED was most certainly the only option for this project and given its success in the TCN studios in Sydney, the Unilumin screen was the logical choice.

Once the product had been chosen, a few of the practical realities had to be overcome. Most LED screens are designed to be flown, not ground supported, but with a nominal load capacity in the studio roof that could barely hang a lighting system, the screen had to be ground supported. Mark Dyson, a name synonymous with set design in Australia, had the unenviable task of creating a set to encompass the expanse of the screen. Also enter Phil Pierdis from Big Picture and Stuart Anderson from Nine who were heavily involved in the design of the screen structure. Taking their experience from the installation in the Sydney studio, Anderson and Pieridis went about developing a design that would not only support the screen, but also allow for an almost 75° curve at the left end (something, it should be pointed out, this particular screen was not designed to do). This task was particularly difficult given the fine pitch. Having only 3.7mm to play with between LEDs meant that particular care had to be taken to maintain the appropriate spacing between panels. Too wide a gap produces a dark line in the image, while too narrow a gap results in a hot spot. Anderson and Pieridis came up with a ground support solution that allowed for the curve and provided the ability to vary the gaps between the panels using nylon wedges.

DOUBLE-DIGIT HI DEF

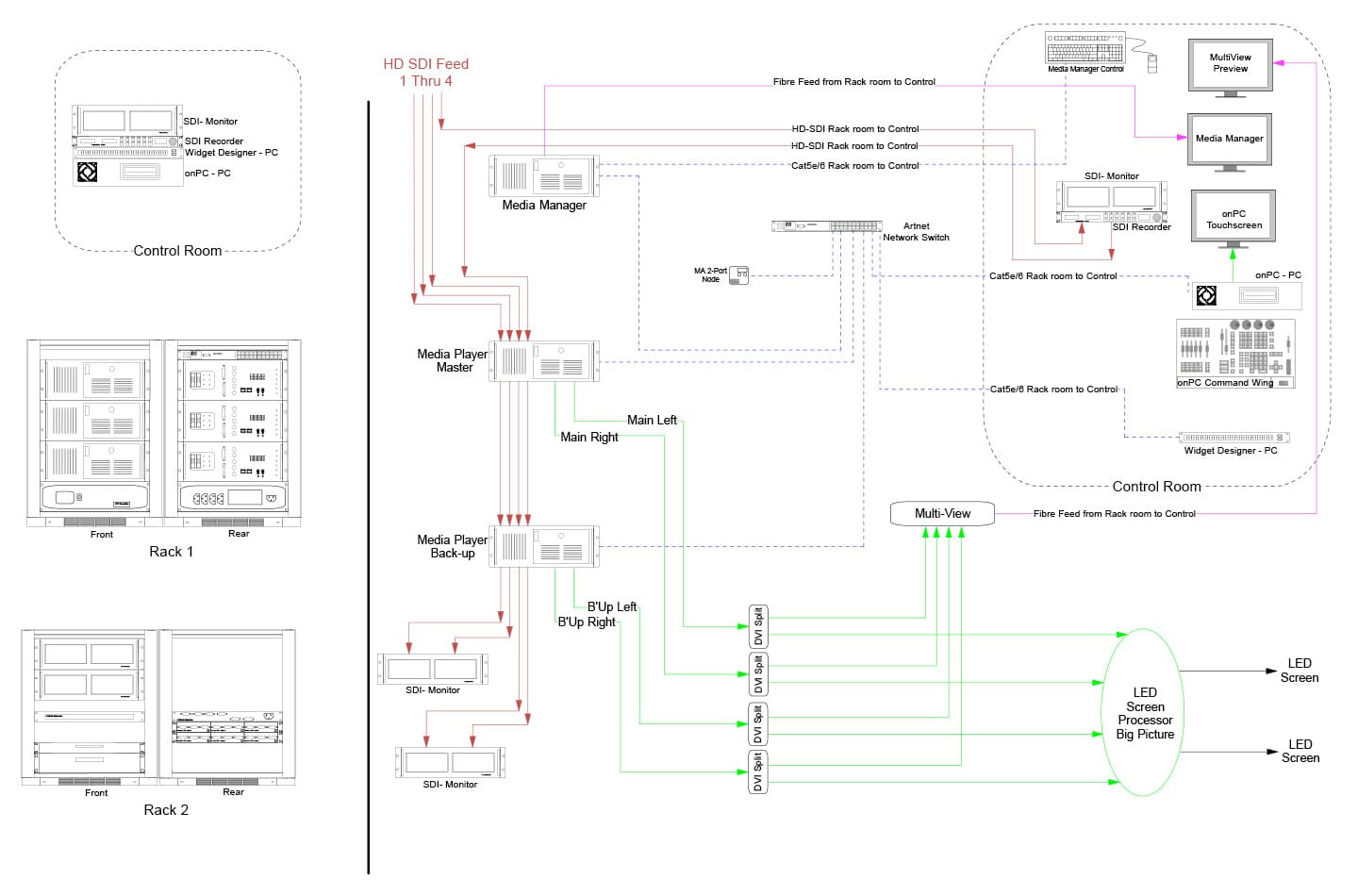

The final screen design had a resolution of 2944 x 512, and with an almost 6:1 aspect ratio it certainly was panoramic, but it posed more than a few problems. With such a massive resolution for a single display, an elegant control solution was required. The fact the screen well exceeded the standard 1920 x 1080 bounds of HD meant that simply routing an HD signal and upscaling it would defeat the purpose of such a high resolution screen. The solution was to use two HD outputs side-by-side on the screen. That way, every pixel would have its own information and the integrity of the screen resolution would be retained. This meant a content map had to be constructed for the custom content. The first inclination was to design in a 2944 x 512 workspace in Adobe After Effects and then break the final content in to two HD feeds for left and right. From there, the two clips would be joined by a replay system.

The problem with this particular solution is that for every complete image on the screen, two separate files were required. Ultimately, it made more sense to place the left hand side of the image at the top of an HD frame and the right side of the image at the bottom. Therefore when searching for content, only one file was required. This made managing the content workflow much easier without compromising the final product.

Choosing a control solution was a more difficult task as there were several aspects of the system that needed consideration. Firstly there was the need to replay custom content to the screen. This custom content included branding of individual sports and generic show branding. These graphics would range from custom content designed specifically for this screen, to standard 16:9 frames that would need to be manipulated to work on the surface. There was also the requirement to route up to four feeds of live vision to the screen at any one time, although today that can be achieved using almost any media server technology. So which one?

STAYING IN CONTROL

The Today Show screen in Sydney is driven by the vision mixer in the control room which works quite well in those circumstances, as the content there is scaled to suit the screen. In the London studio however, the idea was to take full advantage of every pixel, and given that vision switchers generally can’t deal with panning and scanning of multiple images to a single display, it was realised pretty quickly that this would be a job for what is known in the live production industry as a media server.

The Pandoras Box system from Coolux was eventually specified, as in addition to meeting all of the requirements, its capacity to sync multiple sources across a network in real time, and manage content swiftly and easily, made it a standout choice. The addition of a four-way HD-SDI input card meant that four discrete sources could simultaneously be routed to various parts of the screen. So prior to a cross to swimming, a live wide shot of the Aquatic Centre could occupy the left side and the live host on the other. Pandoras Box can also be controlled via DMX as well as its own interface, which is an advantage. This meant that for the late shifts, a single operator could control vision and lighting, while leaving control in the hands of a dedicated operator during the busier times. Ultimately, three MA2 OnPC2 Command Wings ran the studio lighting and media servers for the broadcast.

THE POWER & THE PASSION

Given the very limited mains power available in the studio, most of which had already been consumed by the LED screen, Anderson had trouble finding enough power for a lighting system. Fortunately, the lighting supplier, Panalux UK, was keen to try out a new product they were working on. They were testing out existing 500W and 1kW tungsten Fresnel fixtures that had been retrofitted with an LED source. Inside they bore scant resemblance to a standard Fresnel fixture. The reflector and lamp were replace by an LED array aimed directly along the optical axis of the lens. By using ‘warm white 3200’ LED modules, the light output was so similar to that of a tungsten source that it often had to be pointed out to people that the sources were actually LED and not tungsten. To the naked eye in the studio, one would assume they were traditional fittings – except for the DMX cable that came out of the back.

These fixtures provided a couple of important benefits. Firstly, they alleviated the power problem, as the LED modules required nearly 70% less power to run. Secondly, it eliminated the traditional colour temperature shift during dimming, as LED sources have little colour drift across the dimming cycle. This was even more important given the screen surface behind the presenters maintained a steady colour temperature. Often one can compensate for colour shift by rebalancing the cameras slightly from time to time, however it was no longer even a matter for discussion. Lastly, it also meant the studio didn’t get overly hot with dozens of tungsten light sources burring away. It is interesting to think that almost every light source in the studio, screen included, was an LED. The minor exception was a few energy-efficient fluorescent soft lights. To think that only a few years age LED wasn’t considered a serious light source and would never have been considered for a project such as this.

FEEDING FRENZY

Managing the live feeds to the screens and the general broadcast was no mean feat. At any one time there could be up to 40 different feeds of live sport coming into the studio from the Olympic Broadcasting Service (OBS). OBS is an organisation tasked with the responsibility of covering every sport and sending audio and vision to the various studios for each country at the International Broadcast Centre (IBC). OBS is made up of industry professionals from around the world. It’s not unusual to see the same faces from the past who may have worked on previous Olympics projects. In fact, there are people who have done as many as a dozen Games (including the ‘Winters’) and who are still going strong.

Of course, these sports need to be recorded so they can be replayed for highlights packages or play-on/play-off packages. The industry standard EVS system is a multi-user access system that provides for instant replays and time shifting of content. The EVS team could pull up a highlight from the 100m freestyle final at a moment’s notice and fire it down the line to the input of Pandoras Box. This could be routed to the screen in the studio as a background before being taken full screen for a playoff. EVS could also send still images and slow motion highlights down for backgrounds during quick throws to upcoming sport. Often what was coming from where would be decided literally a second prior to a break ending or coming out of a sport cross. The ability of the EVS system and its operators to quickly supply the appropriate footage meant that the screen content was always fresh, and most importantly, relevant.

PERSONAL BEST

By the closing ceremony, the team in Nine’s London studio had been a part of almost 250 hours of live television in less than three weeks – by any measure, that is a lot of television. The studio team in London played a huge role in that success and may claim to have set a new standard in Australian special event television.

RESPONSES