AV: A Moving Story

Screen Worlds at ACMI introduces our world to the world.

Text:/ Andy Ciddor

Images:/ Courtesy of ACMI

Let’s face it; no one comes into the world of AV because it’s a highly-respected profession or because they wanted to follow in the footsteps of some famous audiovisual hero. Most of us got sucked in by something we saw or did that made us think that it might be something interesting or even fun to do everyday and maybe even make a living out of. The Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), housed in Melbourne’s Federation Square complex is one of the few places in the country where the public is given some insight into the audiovisual world that they’re immersed in.

Starting out in 1946 as the Victorian State Film Centre, it was a resource repository for films, slides, film strips and eventually also audio and video tapes. As ACMI since 2002, it has reinvented itself as a national focus for screening and advocacy, screen education, industry engagement and audience involvement for the moving image (film, television and digital culture). Its programs of screenings, film festivals and exhibitions have striven to give audiences an insight into the culture and technology of their audiovisual environment.

Throughout these changes ACMI has expanded its collection of audiovisual material and through its collaboration with the National Film and Sound Archive, now provides access to one of the country’s most extensive and readily-available collections through the Australian Mediatheque facility. Here you can peruse or study everything from the earliest moving images shot in Australia and most feature films ever made here, all the way through to an extensive collection of international classics and on to contemporary cutting-edge DIY film making.

SCREEN TIME

A major redevelopment completed in 2009 sought to take its engagement with public much further, with the construction of two production studios and a substantial permanent exhibition – Screen Worlds: The Story of Film, Television and Digital Culture. Screen Worlds follows Australia’s engagement with screen culture as both consumer and creator. It’s a huge interactive and immersive exhibition that uses all of the weapons in the audiovisual armoury to illustrate how each of the forms of the moving image have emerged and evolved as powerful creative and influential media. ACMI was helped in the creation of the exhibition by Mitsubishi Electric Australia which provided three years of sponsorship for Screen Worlds that included the direct supply of all 65 projectors and 160 display panels.

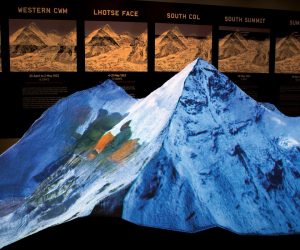

The 1600sqm exhibition employs every available means to communicate with its audience; using historic and highly-recognisable artefacts, some 220 video streams showing on monitors and projection screens, and a series of immersive interactive experiences. The exhibition looks at the evolution of the moving image from three perspectives. Emergence examines how, in not much more than a century, the moving image has changed the world. Voices looks at how Australians have contributed to the development of the moving image, and how the moving image has in turn, influenced who we have become. Sensation uses hands-on, interactive experiences to illustrate core aspects of the moving image: light and shadow, colour and abstraction, sound and vision, and time and motion.

EMERGENCE

Emergence charts the international evolution of the moving image from an Australian perspective. This section moves chronologically through the arrival of each form: film, television, video games, the Internet and beyond into today’s meshed small-screen portable devices. It also highlights key moments and dynamics in moving image history, ending with the question: where will the moving image go next?

Emergence exhibits include a Lumière Cinématographe from 1896, the rare camera/projector that marks film’s arrival, the Rocket Clock, Humpty and Jemima from Play School, the Ned Kelly armour worn by Heath Ledger in Ned Kelly, the original Felix the Cat model, a mechanical television interactive based on John Logie Baird’s original from 1925 drawings, models from Toy Story, an original stumpcam from World Series Cricket, and early video games devices including a Magnavox Odyssey, the first home console. Included in the displays are selections of early film and video equipment that many of us will recall being breathtakingly state-of-the art at the time of its introduction.

(above) Screen Worlds is a world of screens; more that 220 of them, describing, replaying, navigating, interacting and simply displaying the story of screen culture and its impact on our lives. Produced, designed, engineered, programmed and installed in-house, more than 30 hours of vision was curated, written, designed, researched and edited by the ACMI team for this exhibition.

VOICES

Voices offers a look behind the scenes at the creative processes of Australian moving image makers at home and abroad, including the contributions of digital effects creators, famous actors, DIY heroes and indigenous screen talent. Its exhibits include a replica of the iconic Interceptor car from Mad Max, an original canoe from Rolf De Heer’s Ten Canoes, Yoram Gross’ original animation table used to produce Dot and the Kangaroo, Geoffrey Rush’s sword and necklace from The Pirates of the Caribbean, costumes worn by Nicole Kidman in Moulin Rouge! and Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth, film and TV award statuettes, including Oscars, Golden Globes, BAFTAs, AFI Awards and (gasp) Logies, Kylie Minogue and Dame Edna Everage costumes, a giant interactive map that identifies the locations featured in well-known films and TV series, and the piece de resistance: Dexter the Robot from Perfect Match.

What I found most confronting was a display cabinet whose contents include a couple of exposure meters that belonged to Academy Award-winning director of photography, John Seale. One of these was the same model of Seconic meter that I used right up until I got my first digital meter in the early ’90s. It’s pretty devastating to find one of your favourite tools has become a museum exhibit!

SENSATIONS

Sensations is the big-ticket interactive section of the exhibition that features some really fun activities to engage kids and adults at every level of immaturity, and doing so successfully camouflages the learning process. Include are activities such as:

‘Timeslice’ is a Matrix-themed booth equipped with a spiral array of 36 cameras to produce a similar multi-camera slow motion effect to the renowned ‘Bullet Time’ sequences in the Matrix films. The output from your adventures in the booth is saved as a Flash video file and can be emailed to you to for later viewing (as long as you don’t want to watch it on an iPhone or iPad).

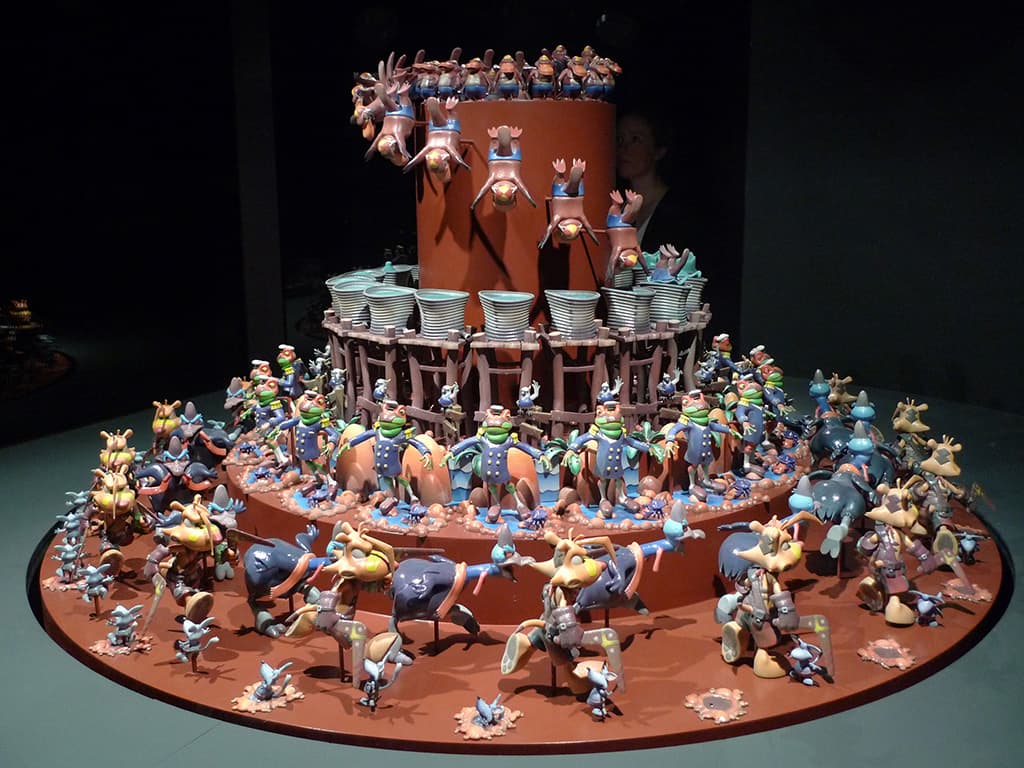

Krome Studio’s TY the ‘Tasmanian Tiger Zoetrope’: a stunning 3D zoetrope with almost 300 different models used to create the illusion, and my personal favourite of the entire exhibition. This exhibit alone is worth the price of entry (which by the way is free).

Anthony Lucas’ ‘The Faulty Fandangle’, where an Oscar-nominated animator combines animation with mechanical illusions and shadow play.

‘Pong vs Tennis’ where you can team up with a friend and play retro-style vs wireless videogame.

‘Flip Book’ is a chance to create a 40-frame flip book ‘animation’ starring yourself and some of your friends and then have it printed in the ACMI Store.

The Sound and Vision Room offers the opportunity to experience how the space of a film can be transformed into a three-screen, surround-sound production with some creative post production. This environment screens excerpts from existing feature films enhanced by collaborations between post house Soundfirm and directors Baz Luhrmann (Australia), Philip Noyce (Dead Calm) and Zhang Yimou (House of Flying Daggers).

‘You and I, Horizontal’ (2006) invites you to step into a dark, haze-filled room and witness Anthony McCall’s 3D sculpture made from projected light.

‘Shadow Monsters’ is a real-time interactive experience. Creatures are formed from the silhouettes of the participants, where the camera captures their shadow and it is input into a computer that transforms the projection into characters by adding shapes to the shadow. Your kids can literally become scared of their own shadow.

GAMES LAB

The fourth section of Screen Worlds is the Games Lab, a fun area for screen gamers, which (although it uses cool big screens for playing such popular games as Quake, Tetris, Civilisation and Pro Evolution Soccer) unfortunately has little or no redeeming social or educational value, and thus probably doesn’t deserve a mention in this article. Except that ACMI has long seen the importance of screen games in the national culture and has been one the few institutions in the world to acknowledge and track their impact.

AV ABOUT AV

Within the overall concepts of the exhibition, each of the thousands of objects and hundreds of image streams has been individually and meticulously designed, researched, assembled and presented. The 220-odd micro-features and micro-documentaries that make up the 30 hours of material on display, have each been researched, written, edited, and mixed by ACMI’s own curatorial and production teams to tell very precise aspects of the big moving image story. The audiovisual components of the exhibition were also specified, acquired, programmed, installed and commissioned by the same ACMI AV staff that are responsible for the exhibition’s care and maintenance. The touchscreen interactive software employed throughout Screen Worlds was also developed in-house. The in-house approach resulted in systems that were designed not only for high quality presentation when the exhibition opened, but for an exhibition that could be maintained at that standard for the very long run, ie. a ‘permanent’ exhibition.

At the heart of this strategy is the use of standardised components throughout. There are only two types of projector in use: the Mitsubishi single-chip DLP WD500U-ST for short throws and the 3LCD Mitsubishi HL2750U for pretty much everything else. Despite the diversity of the exhibition and the large number of screens, there are very few types of video monitors in use: a large 46-inch 16:9 HD display panel, a smaller 32-inch 16:9 monitor, 19-inch and 24-inch 16:9 touchscreens and the in-house developed 10-inch 4:3 monitor with a built-in PC an IR touch bezel.

In the four server rooms, the standard building block that forms the basis for the video displays consists of a commercial off-the-shelf computer with a dual-head VGA card to provide two independent video streams, an RS232 serial port for machine control of the remote projectors, and a USB port for the touchscreen interface. All data feeds (video, audio, USB and RS232) from the server rooms to the exhibits are via baluns over naked Cat6 UTP cable. A library of the hard drive images from each exhibit is held, so when a machine fails it can be replaced by a spare system loaded with the appropriate image

Media is replayed via multiple, synchronised instances of everybody’s very favourite open source media player, the rock-solid, extensible and ever-tweakable VLC (www.videolan.org). The AV department has now become VLC command line wizards.

The two dozen custom and special-purpose projection screens found throughout Screen Worlds are LP Morgan surfaces supplied by Herma.

Most of the low-level localised audio replay is through plastic-box low-budget computer speakers although there are a small number of interesting exceptions. SolidDrive SD1sm surface-mounted transducers are used to turn parts of the interactive Locations Map into sound emitters and Holosonic Audio Spotlights are used in the ceiling above some freestanding exhibits that require substantial sound isolation.

It should be no surprise that exhibition lighting designers Bluebottle used vast numbers of Philips Selecon Aureole profile spots to light the signage and the objects on display without washing out the images on projection screens and LCD panels. Lighting control for the exhibition space is a Philips Dynalite system which was extensively expanded from the original ACMI installation.

A CONNECTION

No matter what your experience and involvement in the audiovisual industry (and unless you found this magazine on a train or in the pile in a waiting room, you probably have some connection, however tenuous), Screen Worlds at ACMI is worth a visit. It’s interesting, engaging, extremely well presented, and an outstanding example of how AV can be used to tell the story of AV.

RESPONSES